Kilimanjaro

10 years ago, in 2006 I worked on a volunteer project in Tanzania. We built 2 new school buildings for an overcrowded school in a remote village.

During our time we got a mid project break, and because we were in Tanzania, and so is the highest mountain in Africa, a group of 7 of us decided the best idea would be to climb it. No one had a smart phone in 2006 (in fact I didn't have a phone at all for the 6 months I was in Africa – 6 months! Now I get a bit panicky if my iPhone and I are in separate rooms! Ugh), so we didn't have access to the internet to do any research. Looking back at this decision, I can confidently say that out of all the ridiculous decisions this is one of the most ridiculous I have ever made.

But the decision was made, we were to get up and down Africa's highest peak in 5 days – the shortest time that is considered 'safe'. All I knew about it was; it's high, there is a bit of ice at the top, it can be a bit chilly.

I didn't have the best start to the trip. My legs were sore, swollen and filled with fluid from many mosquito bites which I had quite a severe reaction to. With every step and bend of my knee I could feel them being uncomfortable, and the allergy tablets I was taking made me drowsy.

We also had a near miss on the way to the mountain, our dala dala (Tanzanian minibus) almost went off the side of the cliff when it lost control on the mud. The man in the red t-shirt, who we called Droopy because he struggled to keep his eyelids up, saved the day and got the bus out of the ditch.

After no research at all we chose the Marangu route, nicknamed the 'Coca-cola' route from the days when you could buy Coca-Cola in the tea huts along the way. Had I been able to do some research I would have found this: "Often selected by unprepared, inexperienced climbers because of its reputation for being the 'easiest' route, it's the shortest and cheapest route, but there is less time to acclimatize, therefore has lower success rates." Great! Not exactly a glowing review, but back then I didn't know any better.

So we rocked up to the base of the mountain in Moshi to meet Kili Willi. We paid him some cash and in return we got a team of porters, guides and a cook. I hired some thermal long johns, gloves and a single pole (not the best kit, it looked like stuff people had abandoned at the end of their trek because it wasn't worth keeping, but better than nothing I guess). Along with my microfleece, waterproof jacket and woolly hat, this was the all the protection I had from the cold weather. Steep learning curve.

At Marangu gate our starting altitude was 1,970m (6,400ft) and we were aiming to get to 5,895m (19,340ft) in less than 72 hours. The ideal way to acclimatise is to not gain more that 300m in altitude per day, trying to sleep lower that you climbed. Looking back I have realised that ascending nearly 4,000m in 3 days is a crazy thing to do! And it's only now, having been to higher altitudes, that I understand the importance of proper acclimatisation and its effects on the body. My research today has found most trips operate on a 6-7 day ascent which is much more realistic / sensible.

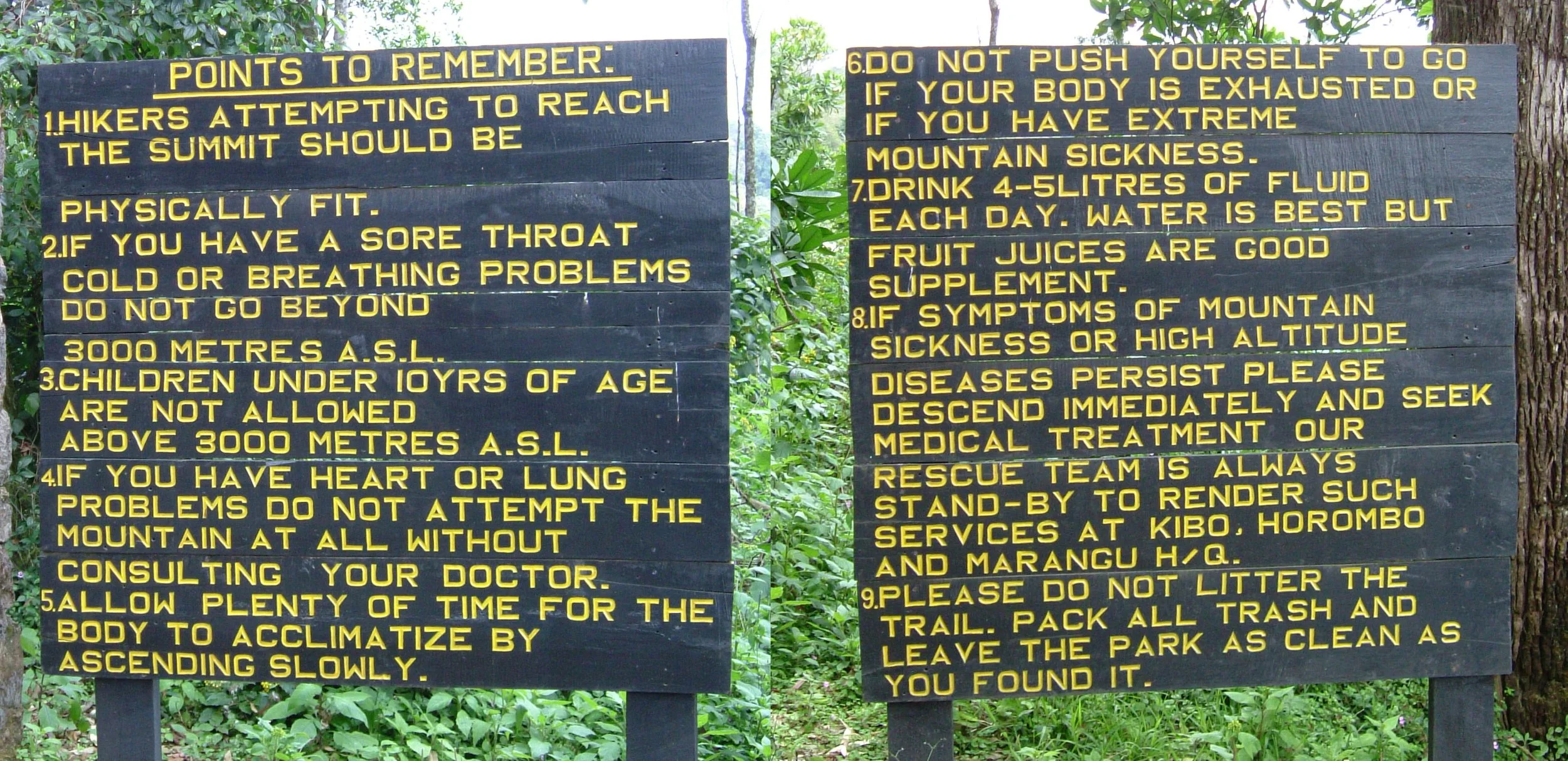

At the start we had a crash course in mountain climbing, and an introduction to altitude sickness actually being a thing we had to think about, from this handy sign with the top 9 points to remember...

This is me and my group at the start. Look at all that cotton clothing! Pretty sure that there wasn't a scrap of technical fabric between us. We actually look like we are on a day trip!

We were operating on African time so we didn't begin walking until about midday. We were all pleasantly surprised by the pace. Pole Pole (pronounced 'polly') was a term used constantly by our guides – meaning slowly slowly. We followed Godfrey and his enormous rucksack through the rainforest and I remember being disappointed that we didn't see any monkeys. The porters carry all your kit, not that I had a lot, and you carry a day bag with water and your essentials. After only 2 hours of walking we stopped for a lunch break. I was already starting to feel rough. Lightheaded and weak. I was fearing altitude sickness already, but I put it down to dehydration and lack of food instead. We had already made it halfway for the day, great! This doesn't seem that hard.

We may not have seen any monkeys but I did have my first encounter with a chameleon, very well disguised so I would have never have spotted him myself being so embarrassingly unobservant...

We were served soup, fried chicken, fruit, bread and boiled eggs for lunch and fully fuelled we walked a further 2 hours to reach Mandara hut (2715m). On arrival we were overjoyed to be greeted with hot drinks, popcorn and biscuits and delighted to be told that popcorn helps acclimatisation (which they also believe in Nepal, and it's a fact that I am yet to be convinced on). But popcorn tastes nice so either way it's a win win situation.

We discovered that there isn't a lot to do halfway up a mountain when it gets dark and becomes a lot colder than you were expecting it to be (being this cold on the first night was concerning to say the least). So we got in our sleeping bags and settled down for the night. You get above the clouds really quickly on this mountain...

In contrast to yesterday we had a 6:30am start to day 2, ready for our estimated 4-6 hours of walking. It was freezing to start but the African sun soon warmed us all up and we were back in our shorts and t-shirts. The sun is a lot more intense up here and I managed to burn the back of my neck to the point of discomfort so I wore my bandana as a neck scarf for the remainder of the trip.

As we sat taking a rest we saw this guy:

He is carrying a stretcher up the mountain (which surely meant that someone had been recently taken down on it — it didn't exactly fill me with confidence). It is however an incredible design. The casualty gets strapped on and with one big wheel in the middle and a person on each of the 4 corners, the stretcher is run down the mountain, normally the main requirement is to lose altitude as quickly as possible — and it works, because we saw someone being run down the mountain on it later on.

We started walking through forest but by the time we reached Horombo huts the vegetation was disappearing with just a few bushes and shrubs remaining. These huts are a lot bigger and busier as people stop here on the way down as well as the way up (the other huts only have to accommodate people on their ascent).

I don't remember too much about today, but back in the days before blogging I kept a written journal and this is what I wrote: "There were very strange toilets at the second hut, like a western toilet but half the size so you still have to squat in an uncomfortable position. They were also disgusting as so many people were using them. There was poo all over one of them, and someone had obviously missed the loo.”

People often see staying in huts as more of a luxury, but from my experience I would now choose camping over huts every time. "We had another nice dinner and went early to bed again. Walking is tiring!

"Day 3 began at 6:30am with a wake up call and a cup of hot Milo while still in our sleeping bags. After breakfast we began walking — the climb is gentle and a lot of the time it doesn't really feel like you're ascending, but the change in terrain happens very quickly. We well and truly left the forest behind today and started walking across a very dry, baron, desert landscape where only a few boulders broke it up. The wind whipped across the open plain and it was so cold.

By the time lunch came I wasn't feeling too good, and although it was 10 years ago I remember how I felt in these next images as if it were yesterday. My head was banging and all I wanted to do was close my eyes and sleep. I was fully prepared to be left there to end my days, I didn't want to take another step. I remember wishing everyone would just shut up and leave me alone — I didn't want them to try and make me walk anywhere. I managed to pick at a bit of chicken but I hardly ate anything. In hindsight, the nausea, headache, lack of appetite and extreme fatigue were all signs of altitude sickness.

But the inevitable couldn't be put off any longer and Beatus made me get up and walk, he even took my bag for me (which after carrying a considerably heavier bag for 5 months along the Pacific Crest Trail just seems so pathetic!).

The last bit of the walk to Kibo hut took forever, I felt so weak I could hardly put one foot in front of the other. But somehow I eventually made it. We were in the same room as a group of Spanish guys who were extremely well prepared, one of them was a mountain leader.

"I remember going straight to bed. I was helped into my sleeping bag and I began to shiver uncontrollably — I thought I had pneumonia or something! The Spanish guy gave me his enormous sleeping bag so I could warm up. This helped, I think he saved my life! Dinner came but I couldn't eat anything. It just made me feel sick. I tried to go to sleep. I think everyone else did the same after they had finished eating. The Spanish man needed his sleeping bag back as he wanted to go to sleep so I had mine and Eds bag for a while, then Beatus swapped his mountain sleeping bag with mine. I think I would have been a lot more ill if he had not done this. It was about 6pm when we all went to be bed, ready for a 12am start in just a few hours time."

I don't know what I would have done without that Spanish man, he was so kind but I can imagine he was thinking how incredibly stupid we were.

They made us get up at 11:30pm, having hardly slept at all this was most unwelcome. "I wasn't really sure how I felt when I woke up. I felt better than I did earlier but still not great — but because I felt so bad before I think I was tricked into thinking I felt better!" I needed to pee, I stumbled around outside to try and find a secluded spot in the baron landscape. My addled mind thought that turning off my head torch would make me invisible to everyone else so I squatted by a rock, unaware that all the people around me who still had their head torches turned on could still see me. Even as they shone their lights on me it still didn't really register. At least I was coherent enough to remember not to go into the long drop / western toilet hybrid, which can only be described as 'splattered with shit' (adventure is never as glamorous as it appears on Instagram!).

We were to begin the ascent at midnight, while the ground was frozen enough to walk on. I was wearing everything I owned and it was woefully inadequate. My friend gave me her scarf. People had already begun their ascent and stretched out ahead of us was a line of tiny lights zigzagging their way up into the darkness.

We set out walking together, and even though we were going very slowly, within about half an hour I was being left behind. We split the group, the others went on with Beatus and I stayed with Hagai. I didn't want to be left alone, I desperately wanted my friends, and my boyfriend, to stay with me, but I would never have ruined someone else's chances of getting to the top, so I watched them go on without me.

Now I was so cold I couldn't feel my feet or my legs and I was struggling to walk. Beatus had given me one of his poles so I now had a pair and he had given his other pole to someone else so he had no poles at all. Although the poles didn't help me walk they were really useful for leaning on. I didn't want to carry on, I would take 2 steps and stop and cry a bit, I would dry heave and vomit a bit, then I would collapse and just sit on the side of the mountain. Hagai must have thought I was a total pain in the ass! But even if he did think that he was still pretty awesome — he rubbed my hands and shoulders to try and keep me warm and stop me falling asleep, he rubbed my legs to try any get some feeling back in them, he tried to make me drink some water, but the water was so cold I didn't want to drink it and he force fed me chocolate to try and keep me going.

My cotton t-shirt, microfleece and waterproof jacket were doing nothing to keep me warm, so Hagai gave me his down jacket that he was wearing. He walked behind me and held on to the sides of my jacket to try and keep me upright and he basically pushed me up the mountain. The sun started to peek over the horizon, I had been on the go for 6 hours, but my memory of it feels like about 2 hours. I led down on the side of the mountain and watched one of the most incredible sunrises I have ever seen. As Kilimanjaro is not in a mountain range the horizon is unbroken and it looks like it goes on forever. It is breathtakingly beautiful.

I lay there for about 20 minutes until the sun rose and I felt its glorious warmth spread through my body. I remember making a promise to myself that I would never complain about being cold ever again — which is a promise I break on an almost daily basis. Now it was light I could see what I had ahead of me — a giant boulder field. There was no way I could make it. I was done.

By now everyone had passed me and I was the last one to reach the top, a few people passed me on their way back down having turned around before making it to the top. They warned me that I should go back, that there were people being sick and someones face was swollen. This was pretty daunting and I just stood and watched them as they passed. I said countless times that I couldn't do it, it was too far, I had no energy — but Hagai was determined to get me up to Gilman's point.

While I was sat there warming up the Spanish guys came by on their return from the summit, they told me I should carry on and make it there. It took me an absolute age, and I have no idea what the time was when I got there, but with Hagai's help I did make it to Gilman's point — only 200m off the summit. He was so determined to get me there, he took my bag and ran up and dropped it off before coming back down and giving me a couple of piggy backs to help me get there. I told him he was crazy, he just smiled and laughed at me.

"When I got there it was amazing. I finally had the chance to look around me and appreciate the view (so far I had just been staring at the ground in front of me). I gave Hagai a big hug to thank him for getting me there. I had been talking to him the whole way but to be honest I don't think he had a clue what I was saying. I had a photo take by a man from Leeds."

I was told by another guide that the rest of my group had left about 20 minutes ago to get to the summit, Uhuru Peak. There was no way I could have made it there, I had not one ounce of anything left to give. I was going to wait there and walk back with them but I was told I should get down as quick as possible so I wouldn't be affected by the altitude any further. So I descended with Hagai and some other randoms, it took a long time to get back to Kibo and I fully appreciated what I had just climbed up and why you had to do it when the ground was frozen. Apart from the big steep rocky bit the ground was loose, which you slid down rather than walked down.

"I got back to the hut and had a much needed lie down and I spoke to the Spanish guys, he said the temperature was -4°c and we were lucky as when he did it last year the temperature was -15°c." Now, as much as I liked that Spanish man, I do have to question his grasp on temperature. I will never know for sure but I am 99.9% sure that it was considerably colder than -4!

Having made it to the summit, the others arrived back at the hut. Beatus told them I had turned back a lot earlier than I did so they were all really surprised and pleased when I showed them the photo of me at Gilman's point. After some soup and an hours rest we made our way back to Horombo just as it started to snow — not that many people can say they have been snowed on in Africa!

We leapfrogged for most of the trip with Lindsay, a crazy American from South Carolina, and 'Uncle Robbie' who was about 4ft tall.

After another night at Horombo we had an easy last day entirely down hill, making it back to the start in about 6 hours. Every step of the descent was like getting a power up, with every metre the air got richer and easier to breathe and after feeling so horrible we started to feel more alive than ever.

My first big adventure taught me a lot.

Throughout my childhood I never really failed at anything, which developed through adulthood into a bit of a fear of failing. My fear has sometimes held me back, I like to be good at things, I like to succeed — if you don't try at something then you don't fail. Right?!

Wrong.

"Success is not final, failure is not fatal: it is the courage to continue that counts."

| Sir Winston Churchill

I've gone on to do some amazing things and it's failure that gave me the intelligence I needed to go on to succeed. After all, trying and failing is better than having never tried at all, and you can always try again.

Today I am a planner and a researcher, maybe as a result of my attempt on Kilimanjaro. I like to know what I am letting myself in for because I never want to be in such a dangerous position ever again!

Kilimanjaro remains unconqured for now. Hopefully one day I will be able to return and finish what I started.